Cloning trick: ligation of multiple inserts

Update: A number of people are finding this post through Google searches. I don't have an updated post on the topic, but if you're trying to assemble multiple DNA fragments then I suggest looking into Gibson Assembly. NEB sells a dead-simple mastermix, which is a bit pricey per reaction (I just make my reactions half the size) but comes out to cheap when you take into account the cost of labor (so long as your P.I. values your time...).

I've spent the last couple of months building a plasmid library, and in the process I thought of a trick. Ligations, perhaps the worst part of cloning, are notoriously finicky reactions. The goal is to take several pieces of linear DNA, where the ends of the pieces can only connect in a certain way, and then use an enzyme (T4 Ligase) to sew them all together into one piece (in my case, a circular plasmid).

Ligase (2HVQ.pdb) rendered in PyMOL.

I needed to insert three fragments at once into a single backbone. In my ignorance (from my lack of experience) I thought ligating four fragments should work just as well as two, so I just threw them all together and ran the reaction. The result was a mess, and when I tested 40 different clones afterwards not a single one was correct. So I started adding them one piece at a time which, obviously, was going to take three times as long.

Though most of what was in my test tube was not the desired product, I figured that there must be some tiny population that actually was the correct fragment. The problem was just that putting my products into E.coli and then trying to find the correct thing wouldn't work if only 1/100 (or fewer!) of the ligation products were correct. But PCR is wonderful for making tiny amounts of DNA into large amounts, so I thought, why not just try to use PCR to get the correct thing out of the mess? Since each product is made out of some combination of the input fragments, the lengths would be discrete and therefore visible and, potentially, separable on a gel. I just needed to be able to copy up enough that I could see DNA run on a gel, and then I could purify out the one that was the right length.

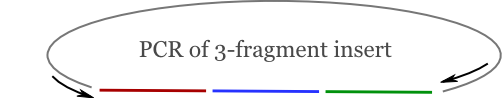

Each differently-colored fragment is being ligated into the gray backbone. The primers (black arrows) flank the entire insert.

I designed primers that would flank the combined insert and did PCR, and did indeed get a band of the desired length! After gel purification I was able to ligate the entire insert into the backbone without any trouble.

You might be asking, "Well isn't this now a two-step process, just one less than the three required otherwise, and so barely worth the effort?" Almost, except that there is no need to transform the multi-fragment ligation mixture. So it's more like 1.5 steps. Plus, the ligation, PCR, gel purification, final ligation, and final transformation can all be done in a single day!

Though my labmates were surprised when this worked, it turns out I was a year too late to publish this idea1.

Footnotes

An, Yingfeng et al. “A PCR-after-ligation method for cloning of multiple DNA inserts.” Analytical biochemistry vol. 402,2 (2010): 203-5. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2010.03.040 ↩